The Water Cycle

Objective

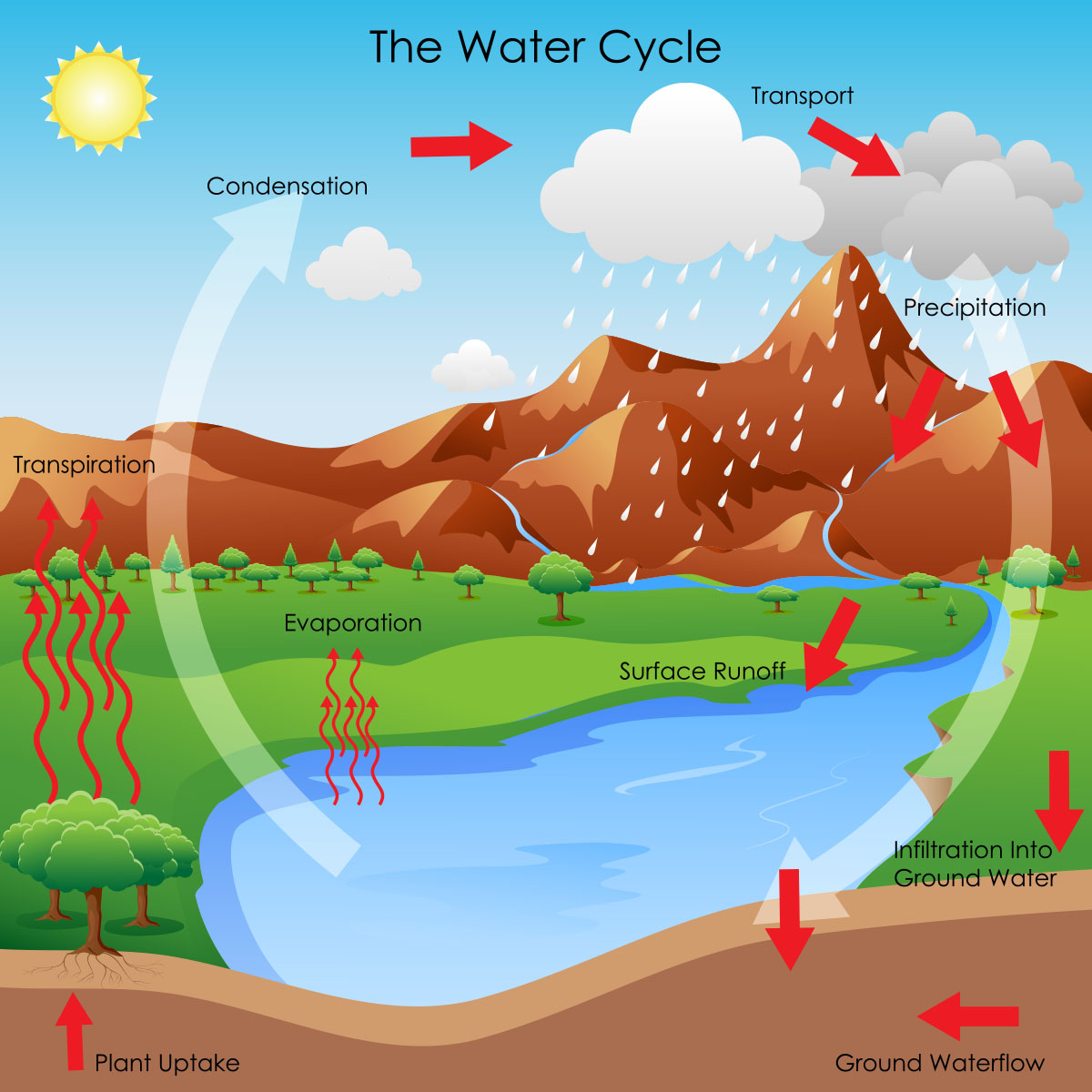

Students will learn about the cycle of water—the important processes of accumulation, evaporation, condensation, and precipitation, and what causes water to move throughout the earth and its atmosphere.

STEAM Connections & Kentucky Academic Standards

NGSS

Earth Systems: Role of Water - K-PS3-1, 2-ESS2-2, 2-ESS2-3, 4-ESS2-2, 4-ESS3-2, 5-ESS2-1, 5-ESS2-2, 6-ESS2-1, 6-ESS2-4, 8-ESS3-1, 8-ESS3-4

Engineering Design

Math

Measurement and Data

Numbers and Operations

Technology

Internet Research

Art

Drawing and Design

ELA

Write and Opinion Piece

Water Resources

Water is found almost everywhere on Earth, from high in the atmosphere (as water vapor) to low in the atmosphere (precipitation, droplets in clouds) to mountain snowcaps and glaciers (solid) to running liquid water on the land, ocean, and underground. Energy from the sun and the force of gravity drive the continual cycling of water among these reservoirs. Sunlight causes evaporation and propels oceanic and atmospheric circulation, which transports water around the globe. Gravity causes precipitation to fall from clouds and water to flow downward on the land through watersheds.

Additional Information:

Introduction

The water you’re drinking might have come out of George Washington’s tooth soaking cup! Before you spit it out, you should know water has been everywhere. Water travels. The water you drink could have come from a volcano, then filtered through a giant sequoia tree, ridden the rapids, evaporated into the atmosphere, turned into grapefruit-size hail, plummeted to the Earth, disappeared into a stream, then circled the world again and again until it ended up in your glass. That’s the water cycle.

The water cycle is the constant movement and storage of water throughout the Earth. The Earth’s water supply never changes. It just travels. The Earth always has 332.5 million cubic miles (1.386 billion cubic kilometers) of water.

In addition to oceans, lakes, and rivers, the Earth stores and transports water in many ways. Water moves through condensation, evaporation, and precipitation (rain and snow). It’s stored in ice, snow, and the ground. Even magma contains water—volcanic eruptions bring water from deep in the earth to the surface. The atmosphere also transports and stores water molecules. A water molecule hangs out in the air for about 10 days before condensing and becoming rain, hail, or even morning dew. Then it continues on its trip around the world.

One way water molecules move around is through evaporation from plants. It’s called transpiration. Think of it as a plant’s version of sweating. Water moves through a plant from the root and eventually evaporates from tiny pores in the leaves. In one year, a large oak tree can transpire 40,000 gallons (151,000 liters) of water!

The process of water “going” into the air is called evaporation. On your paper list some other examples of evaporation. Discuss with your partner what happens to water after it evaporates. Write down what you think. Consider weather and temperature as you list examples.

Activity 1—All Dried Up (Primary)

Materials:

Two dishes

Water - 20 ml

Paper and pencil for each student or a class chart

Procedures:

Get two dishes and put about 10 ml (two teaspoons) of water in each dish.

Place one dish in the sunlight, or if the sun isn’t shining, place the dish under and close to a light source. Place the other dish in the shade.

Observe each dish every 4 hours, then overnight and record what happens to the water.

On the same sheet of paper as above, answer these questions with a partner.

Where did the water go?

From which dish did the water disappear faster?

What caused the water to disappear?

Activity 2—Make a Mini Water Cycle!

Estimated Time: 20-30 minutes for preparation

Materials:

Primary - sandwich-size zip-top bag for each student

Intermediate - 1 gal. zip-top bag

Permanent markers

Blue food coloring (other colors are also fine; let them experiment with color mixing)

Packing tape

½ cup of water

Intermediate only - 8-12 oz. plastic cup

Introduction:

We know that water can be a liquid, a gas, or a solid. Outside, water is always changing from liquid to gas and back again. This process is called the water cycle. You can see how the water cycle works in this activity.

The sun’s heat causes water to evaporate from streams, lakes, rivers, and oceans. The water vapor rises. When it reaches cooler air, it condenses to form clouds. When the clouds are full of water, or saturated, they release some of the water as rain.

Photo courtesy of Greensboro Science Center.

Procedures:

Have students draw the water cycle on the zip-top bag as shown in the examples depending upon grade level. Younger students should draw clouds at the top and water (waves or a line) at about 1½ inches from the bottom. Older students should draw and label collection, evaporation, condensation, and precipitation. They should also use arrows to show how water moves in the bag water cycle.

When the drawings are complete and correct, have younger students place the 1/2 cup of water colored with blue food coloring into the baggy. Older students should place the colored water in the plastic cup and place it in the corner of the bag as shown.

Photo courtesy of San Prudencio English Corner.

Seal the bag tightly then tape it to a sunny window (south-facing) or near a heat source.

You may also experiment by placing the bags in the freezer for a few minutes prior to adding the water, and/or heating the water before placing it in the bag; students will be able to see condensation and a “cloud” much more quickly.

Have students observe what happens inside the bag throughout the day and the next day.

Activity 3—The Water Cycle Game

Based on a game from the University of Alaska Geophysical Institute, this activity models the path water takes through Earth: from soil to rivers and lakes to clouds to the ocean and so on.

Estimated Time: 30 minutes

Materials:

9 six-sided dice

9 Station Information Sheets: Soil Surface, Plant, River, Ocean, Lake, Animal, Ground Water, Glacier, Clouds

Water Cycle Game Student Worksheet, pencil, and brightly colored crayon or marker

Activity Preparation:

Arrange desks or tables in the classroom as shown in the diagram at right. Place one of the Station Information Sheets and a dice on each desk. (NOTE: Alternatively, students can be assigned to draw an illustration for each of the stations.)

Activity Procedures:

Explain that students will play a game; they will role-play water as it moves throughout Earth. Ask students where water exists on Earth and how it gets there. Display “The Water Cycle” graphic.

Distribute the Water Cycle Game Student Worksheet. Divide students into pairs and place them evenly among the stations.

Explain that when the signal is given, students will roll the dice at the station. If more than one student is at a station, students will need to take turns rolling the dice. Students should read the number on the dice and match it to the chart on the sheet on the table. The chart will indicate where to go next. For example, if a student rolls a “3” at the Soil Surface Station, he or she will move to the Ground Water station next.

As students move from station to station, they should chart their paths on their Student Worksheets by placing a “1” where they start.

At the next station, the student should roll the die (at your signal) and move according to the chart to the new station. Each time they move to a new location, they should mark the next sequential number on their worksheet at the proper location and then draw an arrow between their previous location and the new location with a crayon or marker.

Sometimes the chart will indicate that a student should stay at that station. In that case, the student should write a new number on that same location on his or her chart and roll again. Some students may not move to multiple locations, but that is the water cycle!

Play a mock round to make sure students understand the rules.

Indicate that students should begin and assist as necessary. Allow students to play for 10-15 minutes OR roll 10 times. (NOTE: younger students may require more play time.)

Invite students to share the path they took in front of the group. Compare students’ paths.

Ask students to answer the following questions based on the paths that were taken during the water cycle game. List student answers on the board and discuss as a class.

Where can water from a plant go?

How does water get to a river?

Where can water go from a glacier?

How does water get to a cloud?

Critical Thinking Concept: Divide students into pairs or small groups. Assign each group a station. Ask groups to list ways that water is carried or moves from that station to the other stations. Remind students that water does not go to every station, just the ones that are on the chart. For example, water moves from a river to an animal when the animal drinks the water. Ask students to share ideas with the class. See the Water Cycle Information Sheet for more information.

Reading Connections

The Water Cycle - By Rebecca Olien

Water Goes Round: The Water Cycle - By Robin Koontz

There Goes the Water - By Laura Purdie Salas

Inside the Water Cycle - By William Rice

Dive In! Exploring the Science of Water and Food Production - By AFB Foundation for Agriculture

Writing Connection

Based on their game results, ask students to write a narrative of how their water moved through the cycle.

Encourage older students to use water cycle vocabulary words such evaporation, transpiration, precipitation, condensation, infiltration, atmosphere, run-off, and others.

Social Studies and Language Arts

Use the Internet to research related topics, such as:

Which parts of our country have difficulty growing food due to lack of water? - Write an opinion sharing how you feel water usage in the area you choose can be improved.

What are ways farmers conserve and protect water on their farms? - Write an informational text.

Find how much water is used to grow and produce your favorite food? Does the water really get used, or does it move? - Write a narrative to explain how the water moves through the process.

Hands-On Engineering & Design Curriculum Connections

Build a Terrarium - A terrarium is a low-maintenance, miniature garden grown inside a covered glass or plastic container. It is an excellent tool for teaching about the water cycle because it demonstrates evaporation, condensation and precipitation.

Aquifer Model - This activity illustrates how water is stored in an aquifer, how groundwater can become contaminated, and how this contamination ends up in a drinking water source. Ultimately, students should get a clear understanding of how careless use and disposal of harmful contaminants above the ground can potentially end up in the drinking water below the ground. This particular experiment can be done by each student at their work station.

Groundwater Filtration Model - This lesson helps students 1) identify the various parts of the water cycle, 2) identify and explain how groundwater is created, and 3) design and construct an earth system model that will create groundwater.